By Matt Davison

Although I had been inside the Federal Correctional Institution at Terminal Island many times, it was always during the day. Coming into the institution at night is surreal, kind of like going to a night baseball game. You could see clear across the north yard back to where men were playing handball or basketball, and you could see people moving around in their lit cells. The Chaplain who met us at the front entrance escorted John and me into the Chapel, where chairs had already been arranged. A podium and live microphone was also in place. Veterans incarcerated were already lining up to sign in for tonight’s presentation. In the end, sixty Veterans would have signed in and taken a seat.

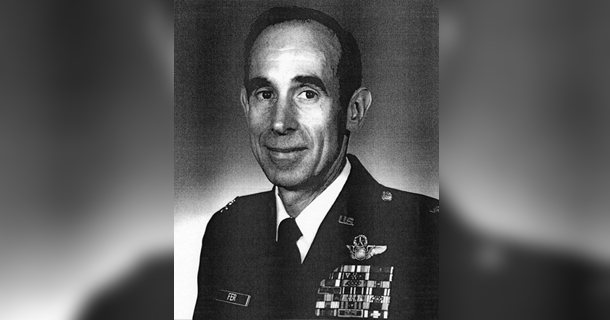

It was February 4, 1967, when Captain John Fer along with six other Airmen were dispatched in a Douglas EB66C Skywarrior over North Vietnam. About 40 miles from the China border, in Bac Thai Province, the aircraft was hit by two missiles from a mobile tracking station, breaking the aircraft in half. Three of the Airmen, including John Fer, were captured. The remains of two others were returned, and one still remains missing. Bleeding from shrapnel wounds and dressed only in shorts and undershirt, John was at first afraid that the prevailing winds might have taken him into China, from which we would never emerge. Fortunately, that was not the case.

Forty-five minutes after touch down, John noticed crowds of people tracking him and waving aged rifles. Marched by the militia along paths lined with peasants holding sickles, he came to a building which was the village head man’s house where a picture of Uncle Ho hung. John breathed a sigh of relief, realizing that he had not been blown into China after all. Chants of war criminal and air pirate filled the air for the three hours it took until a truck, with John’s navigator inside, pulled up and drove the two to Hanoi. It was February, and it was cold.

An interrogator called ‘the Eagle’ came into the room where John sat waiting. The Eagle asked John what his unit was. John responded with name, rank and serial number. He was smacked in the face. The Eagle asked a second time what John’s unit was. Again, John replied with his name, rank and serial number. Again, he was smacked in the face, only harder this time. After a third attempt by the Eagle failed, John was handcuffed and his arms stretched out behind him and strapped in such a way that all circulation was cut off. The eagle left the room and John called out, “okay, I’ll tell you the unit”. The Eagle returned, untied John, and the circulation rushed back. “What was your unit?” “I can’t tell you that”. John was back in the straps again. John later learned that the key to avoiding painful torture was to give false information. But, you had to remember what information you gave because the interrogators took notes.

B-52 bombing runs from Guam frightened the North Vietnamese captors, and provided some breathing space for John and the other POWs. During this time, while in isolation, John began a prayer ritual. From a small piece of rope, he formed a rosary, which became part of a daily ritual of pacing five steps up and back while praying early in the morning, exercising, and praying again. For the North Vietnamese, isolation was key to breaking down allegiance to your country. For the POWs, communications would be instrumental in maintaining their sanity. A 5×5 alphabet matrix was developed, in which communications could be transmitted by tapping on the wall. If the sent message was understood, two taps followed. If not understood, a series of taps followed. It was a simple, yet ingenious way to communicate. On Sundays, during his four months of solitary, church services began camp-wide with a tap on the wall signaling individual recitation of the Lord’s Prayer followed by the Pledge of Allegiance while facing east toward the United States. Before sleep, tapping would spell out “Good Night, God Bless You” (actually spelled out GN, GBU)

Another key to remaining sane was mental exercises. Learning aerodynamics or a foreign language were great ways to maximize quiet time. One POW memorized the 350 names of his fellow POWs alphabetically. John learned Spanish, French, German and Russian during his stay. It was important to occupy your mind. Feeding the spirit was also vital. Each religious denomination had a Chaplain. John McCain was the Presbyterian Chaplain. Every Sunday, there would be church services with an opening prayer, reading of scriptures that were memorized, and hymns that were written by a POW and distributed to all who wished to take part.

In six years, John was only allowed to receive four letters. No packages or photos were given him. A solid spiritual life, faith in God, and exercise kept him in balance. In 1973, it was all over.

In speaking directly to his captive audience, John reminded them that they had a lot in common. They had served this nation, accepted their fate, and would move forward in their lives. He reminded the audience that he and they had many parallels in their life experiences. And he reminded them that we are all sacred, made in God’s image.

One Navy Vet happened to have served with a Captain who John knew quite well. Another Vet asked if he was free to talk. John replied, absolutely not. The code was their only form of communication. The question of one-on-one psychological tactics was raised, and John spoke about the interrogators trying to pit one POW against another. After an interrogation took place, the POW being interrogated tapped out the questions to other POWs so that they could be prepared with their responses. Asked if the survivors held reunions, John replied that they are held every five years. Many are held in Southern California, but they are also held in Washington, D.C., in a Vietnamese restaurant. If you ask John what he missed most during his captivity, his answer would be the sound of children’s laughter. It’s ironic that John would become an elementary school teacher, surrounded by the laughter of children every day.

In terms of advice to the veterans incarcerated in attendance, John advised them to assert their own individuality, stay strong in the face of adversity, and find the balance between the spiritual and the intellectual in their lives. He urged the men not to get caught up in self pity, but to realize that there are many who are far worse off then they. He recalled a moment that he refers to as a miracle, when he was bound in such a way that he thought of himself as a basketball. And he remembers a guard picking him up like a basketball and tossing him into the corner of the room. In excruciating pain, John said a prayer to the Blessed Virgin Mary. When he finished, the guard returned, untied John, and left the room.

The veterans incarcerated referred to John as a hero, which he quickly dismissed, and every one of the 60 in attendance came up for a handshake, hug or autograph. Then, one of the prisoners asked if John would lead them in prayer, which he did without hesitation. The Veterans of FCI Terminal Island will be speaking about the time when John Fer came to visit for a long time to come.